- Informatii telefonice:(+40) 748 400 200

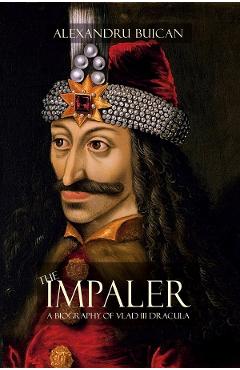

The Impaler. A Biography of Vlad III Dracula - Alexandru Buican

Cod intern: xsales_97345908Producator: Alexandru Buican

Vizualizari: 12 / Achizitii: 10

Stoc: In stoc

Pret: 133.2 RON

Acest produs este publicat in categoria Librarie la data de 01-12-2025: 08:12 si vandut de Libris. Vanzatorul isi asuma corectitudinea datelor publicate. ( alege finantarea potrivita )

-

Produs cu garantie

-

Livrare direct din stocul fizic al Libris

-

Retur gratuit minim 14 zile de la data achizitiei

Many people know the myth of Dracula, but very few know that he was in fact a real person, an fifteenth century ruler of the Romanian people. Still, less people realize that the books they read about the subject are mostly the product of the imagination of the authors. In The Impaler: A Biography of Vlad III Dracula, author Alexandru Buican aims to limit strictly to historical sources Romanians, Hungarians, Turkish, Latin letting them speak for themselves, intending no less then to give the book on the historical Dracula. However uncomfortable may be for the modern reader, the facts about real Dracula’s life are presented with no exaggeration, without any attempt to avoid the psychological fact that made the fifteenth century scholar Mihail Beheim, a contemporary, no refer to the bluntly: From all the madmen and all the/ tyrants I have ever heard of/ in this world/ and under these skies,/ within living memory,/ no other has been more cruel. It is hard to find, during the Middle Ages, a more controversial personality for posterity than Vlad III Dracula. Firstly, because of the nature of the documents historians could use in their attempt to reconstruct his character. A relatively small number of legends complete an equally restricted number of historical documents, gathered in two collections of texts belonging to medieval literature; they originated in Russia and Germany and described the appalling atrocities of the ruler. The Romanian historiography, definitely concerned with the personality of Vlad III, grasped the issue of the relation between these two types of sources from the very beginning. The method chosen by the historian Ioan Bogdan, about a century ago, became traditional in the Romanian historiography. Bogdan divided the documents into two sections: the former included political and diplomatic sources, the latter, literary narratives. This division has been scrupulously kept by Romanian historians to this day. But it requires a choice. The historian is called to decide between using the legends, Russian and German, and leaving them to philologists. This is not possible, because, in the process of reconstructing Vlad III’s individuality, sources cannot be separated. The attitude is not only a matter of method, it has deeper implications. As, it is obvious that the Romanian historiography handles with difficulty the material (the legends) attesting the sadism of the Prince. Despite the fame Vlad III is “enjoying” in the West, based on the legend of his terrifying ferocity, the Romanians feel that he was a rather positive figure of their national history. The rejection of this dichotomic two-headed human being by the Romanian consciousness, as sources bestow, is due, apparently, to a national sensitivity. Nevertheless, in most cases, the authors of monographs about Vlad III have been mainly driven by his celebrity! And his celebrity is not conferred primarily by strictly historical facts (to be found in documents), but just by the legend! The loss, occurring as a result of any refusal of accepting, relies in the fact that the character of Vlad III, complex, but highly uncommon, even for his time, and which cannot be understood at a unilateral reading, remains obscure. With such preconceptions, it goes without saying that you cannot restore that particular psychology (twice), that of an epoch and a (apparently) bizarre man. If we investigate the legend on his behavior, we find out that his barbarism is not very far above that age, an argument strongly invoked by Romanian historians! What then? Did contemporaries try, by insisting on cruel facts and on the bloody nature of the Romanian ruler, to really express their bewilderment when confronted with an entity beyond their understanding? That particular psychology, imposed to his contemporaries, is the aim of the present book to try to explain first and foremost. We are not afraid to admit Vlad III’s cruelty and it is not our intention to add another work which exonerates him of the legend, we intend to reveal and understand the inner complex of the voivode. Moreover, trying to present his civil status, besides the "heroic” data about the historic figure, and even more intimate details, we have sought to delineate an inner portrait of the famous and frightful man. In investigating Vlad III’s identity, we have decided to solve the dilemma of the sources, considering the legends as documentary material, both factual and psychological, and use them integrated into the narrative epic. Another feature of the Romanian monographs is that they are devoid of large quotations from documents. But this is exactly the essence of the historical evocation. No matter the authority (or talent!?) of an author, a mere narration of facts does not convince. In the long run, the narrative gives way to stories and arouses mistrust. History is not made up of statements, but of evidence. Narratives with no documentary base are not authoritative. Any document carrying energies of 14th century human wills shakes the soul. Therefore, abundantly quoting the sources means leaving the documents (historical and literary) "speak" by themselves, in our opinion the most honest way to elucidating the "psychological mystery of Vlad III Dracula (the Impaler)". Last, but not least, our intention is to put this translation of a corpus of documents, hardly accessible in any other language, except Romanian, at the disposal of those interested in Vlad III’s singularity.

Scrie parerea ta

The Impaler. A Biography of Vlad III Dracula - Alexandru Buican

Ai cumparat produsul The Impaler. A Biography of Vlad III Dracula - Alexandru Buican ?

Lasa o nota si parerea ta completand formularul alaturat.

Many people know the myth of Dracula, but very few know that he was in fact a real person, an fifteenth century ruler of the Romanian people. Still, less people realize that the books they read about the subject are mostly the product of the imagination of the authors. In The Impaler: A Biography of Vlad III Dracula, author Alexandru Buican aims to limit strictly to historical sources Romanians, Hungarians, Turkish, Latin letting them speak for themselves, intending no less then to give the book on the historical Dracula. However uncomfortable may be for the modern reader, the facts about real Dracula’s life are presented with no exaggeration, without any attempt to avoid the psychological fact that made the fifteenth century scholar Mihail Beheim, a contemporary, no refer to the bluntly: From all the madmen and all the/ tyrants I have ever heard of/ in this world/ and under these skies,/ within living memory,/ no other has been more cruel. It is hard to find, during the Middle Ages, a more controversial personality for posterity than Vlad III Dracula. Firstly, because of the nature of the documents historians could use in their attempt to reconstruct his character. A relatively small number of legends complete an equally restricted number of historical documents, gathered in two collections of texts belonging to medieval literature; they originated in Russia and Germany and described the appalling atrocities of the ruler. The Romanian historiography, definitely concerned with the personality of Vlad III, grasped the issue of the relation between these two types of sources from the very beginning. The method chosen by the historian Ioan Bogdan, about a century ago, became traditional in the Romanian historiography. Bogdan divided the documents into two sections: the former included political and diplomatic sources, the latter, literary narratives. This division has been scrupulously kept by Romanian historians to this day. But it requires a choice. The historian is called to decide between using the legends, Russian and German, and leaving them to philologists. This is not possible, because, in the process of reconstructing Vlad III’s individuality, sources cannot be separated. The attitude is not only a matter of method, it has deeper implications. As, it is obvious that the Romanian historiography handles with difficulty the material (the legends) attesting the sadism of the Prince. Despite the fame Vlad III is “enjoying” in the West, based on the legend of his terrifying ferocity, the Romanians feel that he was a rather positive figure of their national history. The rejection of this dichotomic two-headed human being by the Romanian consciousness, as sources bestow, is due, apparently, to a national sensitivity. Nevertheless, in most cases, the authors of monographs about Vlad III have been mainly driven by his celebrity! And his celebrity is not conferred primarily by strictly historical facts (to be found in documents), but just by the legend! The loss, occurring as a result of any refusal of accepting, relies in the fact that the character of Vlad III, complex, but highly uncommon, even for his time, and which cannot be understood at a unilateral reading, remains obscure. With such preconceptions, it goes without saying that you cannot restore that particular psychology (twice), that of an epoch and a (apparently) bizarre man. If we investigate the legend on his behavior, we find out that his barbarism is not very far above that age, an argument strongly invoked by Romanian historians! What then? Did contemporaries try, by insisting on cruel facts and on the bloody nature of the Romanian ruler, to really express their bewilderment when confronted with an entity beyond their understanding? That particular psychology, imposed to his contemporaries, is the aim of the present book to try to explain first and foremost. We are not afraid to admit Vlad III’s cruelty and it is not our intention to add another work which exonerates him of the legend, we intend to reveal and understand the inner complex of the voivode. Moreover, trying to present his civil status, besides the "heroic” data about the historic figure, and even more intimate details, we have sought to delineate an inner portrait of the famous and frightful man. In investigating Vlad III’s identity, we have decided to solve the dilemma of the sources, considering the legends as documentary material, both factual and psychological, and use them integrated into the narrative epic. Another feature of the Romanian monographs is that they are devoid of large quotations from documents. But this is exactly the essence of the historical evocation. No matter the authority (or talent!?) of an author, a mere narration of facts does not convince. In the long run, the narrative gives way to stories and arouses mistrust. History is not made up of statements, but of evidence. Narratives with no documentary base are not authoritative. Any document carrying energies of 14th century human wills shakes the soul. Therefore, abundantly quoting the sources means leaving the documents (historical and literary) "speak" by themselves, in our opinion the most honest way to elucidating the "psychological mystery of Vlad III Dracula (the Impaler)". Last, but not least, our intention is to put this translation of a corpus of documents, hardly accessible in any other language, except Romanian, at the disposal of those interested in Vlad III’s singularity.

Acorda un calificativ